Rwandan Civil War

| Rwandan Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

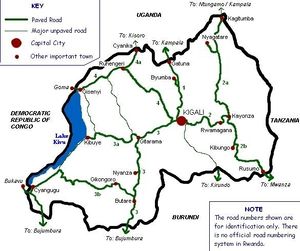

Map of Rwanda with towns and roads |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Rebels:

|

Government:

Also:

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 25,000 rebel troops | 200,000 government troops | ||||||

The Rwandan Civil War was a conflict within the Central African nation of Rwanda between the government of President Juvénal Habyarimana and the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). The conflict began on 2 October 1990 when the RPF invaded and ostensibly ended on August 4, 1993 with the signing of the Arusha Accords to create a power-sharing government.[1]

However, the assassination of Habyarimana in April 1994, when his plane was shot down as it was preparing for a landing at Kigali, proved to be the catalyst for the Rwandan Genocide, the commonly quoted death toll for which is 800,000. The closely interrelated causes of the war and genocide led some observers to assume that the reports of mass killings were in fact some new flaring of the war, rather than a different phase. The RPF restarted their offensive, eventually taking control of the country. The Hutu government-in-exile then proceeded to use refugee camps in neighboring countries to destabilize the new RPF government. The RPF and its proxy rebel forces prosecuted the First Congo War (1996-1997), which led in turn to the Second Congo War (1998-2003), all of which involved a Hutu force with the objective of regaining control of Rwanda. Thus while the civil war officially lasted until 1993, some literature have the war ending with the RPF capture of Kigali in 1994 or with the disbanding of the refugee camps in 1996, while some consider the presence of small rebel groups along the Rwandan border to mean that the civil war is ongoing.

Contents |

Background

The ethnic tensions between the Hutu majority and the Tutsi minority had their roots in the Belgian colonial era, where the ruling Belgian authorities empowered the Tutsi aristocracy, and cemented the second class status of Hutus, in what had previously been a moderately fluid social dynamic. Upon leaving Rwanda, Belgian diplomats stirred the pot by reversing their favoritism, encouraging nationalist Hutu uprisings in the name of democracy. Episodes of violent attacks and reprisals between Hutus and Tutsis flared up in the first two decades of Rwanda's independence, leaving smoldering tensions and resentments[2].

The level of ethnic and political tension increased in 1990. Discontents were exacerbated by a slumping economy and food shortages; throughout the year, the country had to endure bad weather and falling coffee prices. The tense political situation became tenser after the President of France called for greater democracy in Francophone Africa. France, though not traditionally associated with Rwanda, began to show that it would apply political pressure if Rwanda didn't make concessions to democracy. Many Rwandans heard the call and began forming a democracy movement, which protested during the summer.

Grumblings of the Tutsi diaspora contributed to the tension. Tutsis who had been exiled for over thirty years were coalescing in an organization known as the Rwandese Patriotic Front (RPF). The Hutus in Rwanda considered these Tutsis to be an evil aristocracy that had rightly been exiled. They observed that the descendants of these Tutsis no longer had any knowledge of Rwanda, and spoke English instead of French. The exiled Tutsis, however, demanded recognition of their rights as Rwandans, including, of course, the right to return there. These Tutsis began to pressure the Rwandan government, and eventually obliged the Habyarimana government to make concessions. The RPF was under the command of Major-General Fred Rwigema, who had risen to be deputy minister of defense in Uganda. However, growing xenophobia had led to his removal and new legislation that prohibited non-Ugandan nationals, including Rwandan refugees, from owning land in Uganda. It was this "push" factor from Uganda, as much as the "pull" of their ancestral homes, that led the RPF to fight for citizenship in Rwanda.[3]

Habyarimana found himself compelled to set up a national committee to examine the "Concept of Democracy" and to work on the formation of a "National Political Charter" which would help reconcile the Hutus and Tutsis. At this crucial stage in negotiations the situation deteriorated. The RPF was simply unwilling to wait any longer for the Rwandan government to deliver on its promises.

Failed 1990 invasion

At 2:30 pm on October 1, 1990 fifty RPF rebels crossed the border from Uganda, killing customs guards. They were followed by hundreds more rebels, dressed in the uniforms of the Ugandan national army. The rebel force, composed primarily of second-generation Tutsis, numbered over four thousand troops who were well-trained in the Ugandan army and had combat experience from the Ugandan Bush War. The RPF rebels, organized in a clandestine cell structure, had simply deserted their posts and taken their weapons with them. RPF demands included an end to ethnic segregation and the system of identity cards, as well as other political and economic reforms that portrayed the RPF as a democratic and tolerant organization seeking to depose a dangerous and corrupt regime.[3] Both President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda and President Habyarimana of Rwanda were in New York attending the United Nations World Summit for Children.[4] The role of Uganda was immediately brought into question. Museveni, in a conference with fellow African heads of state years later, stated that the RPF had launched the invasion "without prior consultation" and "faced with [a] fait accompli situation by our Rwandan brothers," Uganda decided "to help the Rwandese Patriotic Front (RPF), materially, so that they are not defeated because that would have been detrimental to the Tutsi people of Rwanda and would not have been good for Uganda's stability."[5]

Originally the 1500 men[4] of the invading force made good progress against the numerically superior but poorly trained soldiers of the Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR), which numbered only 3000-4000 itself.[4] However RPF commander Fred Rwigema was killed by his subcommander Peter Bayingana on the third day of the war.[6] Nevertheless, on October 4 the government called upon Belgium for assistance as the RPF offensive advanced to Gatsibo and Gabiro, about 45 miles from Kigali.[4]

On the night of 4 October, the Rwandan government staged a fake attack on Kigali, complete with gunfire and explosions around the city. This piece of theater was intended to frighten the populace into supporting the war and encouraging the reporting of suspected RPF sympathizers among the Tutsi. Over 10,000 people were arrested. The reaction also included directed killing. A witness testified that, on October 2, para-commandos under Major Aloys Ntabakuze separated civilians fleeing the fighting at Umutara into Hutu and Tutsi, and used grenades to kill the Tutsi. Eight days later, another witness testified that Ntabakuze ordered the ethnic cleansing of a village called Bahima. Ten days after the invasion, local officials in Kibilira were told to kill the local inyenzi and burn down their homes because of the threat of the RPF offensive. At least 348 civilians were killed in 48 hours.[7]

The offensive failed in large part due to the forces sent by Zaire and France to support their ally. Several hundred troops of the elite Zairian Special Presidential Division (DSP) arrived. France rushed the 1st and 3rd companies of the 8th Marine Infantry Parachute Regiment, consisting of 125 men, from the Central African Republic in Operation Noroît.[8][9] It also shipped artillery, mortars and other materiel to Rwanda, stating that they were countering "aggression launched from an English-speaking country."[10] France, which had signed a defense pact with Habyarimana in 1975, insisted that its forces had been deployed strictly to protect its nationals, but the parachute companies set up positions blocking the RPF advance to the capital and airport. Col. René Galinié had command of the initial deployment, but was replaced by Col. Jean-Claude Thomann on the 19th of October. Operation Noroît would eventually include parts of the 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment, 3rd Marine Infantry Parachute Regiment and 13th Parachute Dragoon Regiment.[9] At first, Belgium also supported the government but cut all lethal aid shortly after hostilities began, citing a domestic law prohibiting their military from taking part in a civil war. France, in contrast, saved the regime and gave significant military and financial support, thus replacing Belgium as Rwanda's major foreign sponsor.[10][11]

On October 7 the government forces launched a counter-offensive, sending in 5200 soldiers.[12] The RPF who had only prepared for a short war began to fall back when it became clear that they did not have the heavy equipment needed to face the government forces in a conventional conflict. Major Paul Kagame, who was in the United States taking a course at the Command and General Staff College, was contacted and returned to take control of the rebel forces. To make matters worse, on 23 October two more RPF commanders, Maj. Peter Bayingana, who had taken de facto command, and Chris Bunyenyezi, were arrested by Salim Saleh, the Ugandan president's brother, for the murder of Rwigyema and brought back to Uganda for interrogation and eventual execution.[6] The RPF force was thrown into confusion and by the end of the month, had been pushed back into Akagera National Park in the northeast corner of the country.[13][14] French spotter planes were used to find retreating RPF units so they could be destroyed by the FAR.[11]

On his arrival Paul Kagame began to reorganize his forces, which had been reduced to less than 2000 troops, and decided to develop a guerrilla style war in the north of the country. He pulled his forces back into Uganda and then moved them into the forested Virunga mountains.[15][13] The RPF spent two months in this area, without engaging the government forces. This time was spent reorganising the army and rebuilding the leadership that had suffered so much during the fighting. During this time the RPF also benefited from the recruitment of men from the Tutsi diaspora, in particular the Banyamulenge of Zaire, who were increasingly the targets of local discrimination. Therefore by early 1991 the RPF had grown to 5,000 men, by 1992 it had reached 12,000 and by the 1994 genocide numbered 25,000.

Guerilla war

In order to kick start the guerrilla war, Kagame planned an audacious attack on the northern town of Ruhengeri. This had the aim of targeting a city in the north, a stronghold of the Habyarimana regime, as well as spreading insecurity to other towns throughout the country. On 23 January 1991 the RPF captured Ruhengeri, freeing numerous political prisoners and capturing a large amount of weapons and equipment, before retreating back to the forests that evening.

Following this action the RPF withdrew and began to carry out a classic hit and run style guerilla war. Low intensity fighting dragged on with neither side managing to inflict any major defeats on the other. The RPF started broadcasting from Uganda into Rwanda on its own radio station, called Radio Muhabura in 1991. It was monitored by the BBC starting in 1992, and was mostly a propaganda instrument for the RPF. It accused the Habyarimana government of genocide as early as January 1993, even before the Arusha accords. Over the next few years there were numerous attempts at ceasefires, though they achieved little and the fighting continued until 13 July 1992 when a cease-fire was signed in Arusha. Over the course of the following months negotiations continued, though without any serious breakthroughs and with the tension on both sides mounting. Finally, following reports of massacres of Tutsis, the RPF launched a major offensive on 8 February 1993.

This offensive forced the government forces back in disarray, allowing the RPF to quickly capture the town of Ruhengeri, and then to turn south and begin advancing on the capital. This caused panic in Paris (a long term supporter of the Habyarimana regime) which immediately sent several hundred French troops to the country along with large amounts of ammunition for the FAR artillery. The arrival of these French troops in Kigali seriously changed the military situation on the ground. Implicit in their support for the government and their rapid deployment was the threat that, should the RPF advance on the capital, then they may find themselves fighting French paratroopers as well as Rwandan government soldiers. On 20 February, with the RPF only 30 km north of Kigali, the rebels declared a unilateral ceasefire and over the following months pulled their forces back. By that time, over 1.5 million civilians, mostly Hutu, had left their homes, fleeing the mass murders conducted by the RPF troops towards the Hutu population.

An uneasy peace was once again entered into, which would last until 7 April of the following year. Over the following months the peace process developed. One of the stipulations of the agreement was that the RPF would station a number of diplomates in Kigali at the CND parliament building. These men were to be protected by between 600-1000 RPF soldiers.

The Tutsi diaspora miscalculated the reaction of its invasion of Rwanda. Though the Tutsi objective seemed to be to pressure the Rwandan government into making concessions which would strip Tutsis of their largely 'second class' status, the invasion was seen as an attempt to bring the Tutsi ethnic group back into power. The effect was to increase ethnic tensions to a level higher than they had ever been. Hutus rallied around the President. Habyarimana himself reacted by instituting genocidal programs, which would be directed against all Tutsis and against any Hutus seen as in league with Tutsi interests. Habyarimana justified these acts by proclaiming it was the intent of the Tutsis to restore a kind of Tutsi feudal system and to thus enslave the Hutu race.[16]

Arusha accords

The war dragged on for almost two and 1/2 years until a cease-fire accord was signed July 12, 1992, in Arusha, Tanzania, fixing a timetable for an end to the fighting and political talks, leading to a peace accord and powersharing, and authorizing a neutral military observer group under the auspices of the Organization for African Unity. A cease-fire took effect July 31, 1992, and political talks began September 3, 1992.

Military operations during the 1994 genocide

- This section details the conduct of the war during the 1994 genocide. For details of the genocide itself, see Rwandan Genocide.

On 6 April 1994 president Habyarimana was returning from Arusha when his presidential jet was shot down, killing all inside. That night elements of the Interahamwe and the presidential guard began to kill opposition politicians and prominent Tutsis. Over the following days it became clear that the target of these killings was the entire Tutsi population along with certain moderate Hutus. The Rwandan Genocide had begun and would last three months, killing hundreds of thousands of people, about 937,000 according to the RPF.

The nature of the genocide was not immediately apparent to foreign observers, and was initially explained as a violent phase of the civil war. Mark Doyle, the correspondent for the BBC News in Kigali, tried to explain the complex situation in late April 1994 in these words,

Look, you have to understand that there are two wars going on here. There’s a shooting war and a genocide war. The two are connected, but also distinct. In the shooting war, there are two conventional armies at each other, and in the genocide war, one of those armies, the government side with help from civilians, is involved in mass killings.[17]

By evening on 7 April with killings becoming widespread and the RPF battalion in the parliament building coming under attack, the RPF renewed its offensive south. The RPF troops within the parliament building, having dug strong defences during the previous months, in case they were caught in the capital with their supply lines cut and under attack, were engaged by the Rwandan army in the nearby army camp at Kanombe, near the airport. The rebel forces within the parliament complex, commanded by Lt Col Charlis Kayonnga, began to fight their way out and began to attack the surrounding government-held districts. Their primary focus, however, was to move north and link up with the main rebel army.

The main RPF forces in the north began a three pronged attack on the morning of 8 April. One group moved west to Ruhengeri and Char Mobile Force commanded by col Gashumba engaged government forces there, although they would make little progress and were more likely a defensive force securing the right flank of the RPF advance south. The second group under command of Colonel Eugen Bagire was Commanding officer 7th Battalion and Lieutenant-Colonel Fred Ibingira was the Commanding officer of the 157 Battalion moved down the eastern border of the country towards Kibungo. The third group with the Commanders Colonel Sam Kaka was commanded ALFA Mobile Force, Colonel Charlis Ngoga Commanding officer of the 59th Battalion, 21st Battalion was Commanded by Col musitu, Charles Muhire was Commanding officer of the 101 Battalion and Bravo Mobile Commanded by Ludovic Twahirwa known as Dodo really main RPF advance was towards the capital, which they managed to reach by the evening of 11 April. Both sides began to reinforce and strengthen their positions, with the RPF beginning a slow but effective encirclement of the city. On 12 April the provisional government fled to Gitarama to attempt to escape the fighting.

In the east the RPF faced little government resistance and reached the Tanzanian border on 22 April. However, with almost all of the RPF's heavy equipment focused on the battle for Kigali, the western advance on Ruhengeri stalemated.

In the capital, the RPF advance continued its slow yet methodical encirclement of the city, forcing the airport to close on 5 May due to intense shelling. A further sign of the success of Kagame's troops was the cutting of the Kigali-Gitarama road on 16 May. This was followed six days later by the capture of Kigali International Airport. In an attempt to reverse the defeats that it was suffering, the FAR launched a counter-attack on 6 June, although this was halted almost immediately and failed to achieve any significant gains.

The RPF forces, having control of the northern, eastern and southern suburbs, began to move north around the south-western edge of the city. This put further pressure on Gitarama which fell on 13 June. At this point the RPF began to close in on the center of the capital, hoping to defeat the government forces in the field. This took the form of putting pressure on three sides of the city with infantry and light artillery and mortars, allowing the defenders no respite. Heavy fighting continued through June and into the first week on July. However, on 3 July the government forces began to withdraw from the capital, taking with it the majority of the civilian population. According to UN sources they had almost completely run out of ammunition. The following day, after a three-month long battle, the RPF moved in and captured the entire city.

In the meantime the RPF's eastern forces had reached the south eastern edge of the country and then swung on an axis, hinged on Kigali, westward. Through June they pushed the government west through the southern region, along the border with Burundi. They finally stopped following their capture of Butare on 2 July and the arrival of the French, who blocked their path with the implementation of Opération Turquoise.

With the fall of Kigali the government forces began to disintegrate. The army lost cohesion and began to rout, being closely pursued by the RPF. This made defending the last two northern towns of Ruhengeri and Gisenyi almost impossible. With his forces in the capital now freed up from the battle for Kigali, Kagame moved the bulk of his army north to capture the government's power base. On 13 July Ruhengeri finally capitulated, followed on 18 July by Gisenyi.

In the south-west of the country French forces from Operation Turquoise controlled a large area, which was given over to the RPF on 21 August 1994, thus giving the RPF complete control of the country.

Post-genocide

The Tutsi rebels defeated the Hutu regime and ended the genocide in July 1994, but approximately two million Hutu refugees - some who participated in the genocide and feared Tutsi retribution - fled to neighboring Burundi, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zaire. Thousands died in epidemics of cholera and dysentery that swept the refugee camps. The international community responded with one of the largest humanitarian relief efforts ever mounted. The Rassemblement Démocratique pour le Rwanda, composed of Hutu troops and militia members, began to militarize the camps, using them as bases to overthrow the new Kagame government.

Its patience exhausted, Rwanda sponsored an invasion of Zaire in 1996. Its chosen proxy force was the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (AFDL) led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila. The AFDL and Rwandan forces, supported by Uganda, cleared the border refugee camps easily. However, many Hutu militants fled westwards, away from the border. The AFDL followed behind, marching towards Kinshasa as the regime of Mobutu Sese Seko collapsed. The AFDL overthrew the government and Kabila proclaimed himself the new president of the renamed Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in May 1997.

Kabila soon turned on his Rwandan and Ugandan supporters, who reinvaded the DRC in 1998 to overthrow Kabila. Kabila formed an alliance with the Army for the Liberation of Rwanda, the successor organization to the Rassemblement Démocratique pour le Rwanda. After Kabila was assassinated in 2001 and his son Joseph became president, Hutu militants reformed into the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR).

The war, the deadliest since World War II, officially ended in 2003. However, the remnants of the FDLR and possibly other Hutu militants maintain a presence in eastern Congo. While not strong enough to pose a threat to the Kagame government, they continue to destabilize the Rwanda-DRC border region.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Timeline: Rwanda", BBC News, 8 August 2008; to support wording "ostensibly ended"

- ↑ Gourevitch, Phillip. We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will be Killed With our Families. Picador. ISBN 0-31224-335-9.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Linda Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder: The Rwandan Genocide, Verso: New York, 2004, ISBN 1-85984-588-6, pp. 13-14

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Rwanda calls for aid to halt rebels" by Robert Biles, The Guardian, October 4, 1990

- ↑ Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, Princeton University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-691-10280-5, p. 183

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Gérard Prunier, Africa's World War, Oxford University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-19-537420-9, p. 13-14

- ↑ Melvern 2004, pp. 14-15

- ↑ "Chronologie d’une collaboration française avec l’état rwandais", hikabisa.com (French)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Motifs et modalités de mise en oeuvre de l’opération Noroît", Voltaire Network, 15 December 1998 (French)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Why Hutu and Tutsi Are Killing Each Other: A Rwanda Primer" by Frank Smyth, franksmyth.com, April 24, 1994

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Melvern 2004, p. 14

- ↑ Melvern, A People Betrayed, Zed Books, 2000, pp 29 (

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Interview with Kagame - Habyarimana Knew Of Plans To Kill Kim" by Charles Onyango-Obbo, The Monitor, December 19, 1997

- ↑ Timeline: Emergency situations and their impact on the Virunga Volcanoes, World Wildlife Fund

- ↑ Melvern, A People Betrayed, Zed Books, 2000, pp 27-30 (excerpt hosted by orwelltoday.com)

- ↑ Destexhe, Alain. Rwanda and Genocide in the Twentieth Century, 1995. Page 46.

- ↑ Transcript of remarks by Mark Doyle in Panel 3: International media coverage of the Genocide of the symposium Media and the Rwandan Genocide held at Carleton University, 13 March 2004

External links

- Rwanda Civil War, globalsecurity.org

- Human Rights Developments in Rwanda, Human Rights Watch report of 1992

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||